Il giorno 22 dicembre 2021 è stato pubblicato sulla Gazzetta Ufficiale (G.U. n. 303) il Decreto del 18 novembre 2021 che approva le “Linee guida per l’identificazione delle aree definibili come boschi vetusti” e la conseguente creazione della Rete Nazionale dei Boschi Vetusti (come da art.7 comma 13-bis, del decreto legislativo 3 aprile 2018, n. 34; Testo unico in materia di foreste e filiere forestali - TUFF). Le linee guida allegate al Decreto delineano i requisiti fondamentali che devono avere i popolamenti forestali per essere considerati boschi vetusti, ovvero:

- superficie di almeno 10 ha;

- presenza di specie autoctone spontanee coerenti con il contesto biogeografico;

- biodiversità caratteristica conseguente all’assenza di disturbi da almeno sessant’anni [1];

- presenza di stadi seriali legati alla rigenerazione e alla senescenza spontanee.

A questo punto le Regioni e le Province autonome sono chiamate a stabilire, in relazione al proprio assetto amministrativo, l’iter di riconoscimento dei “boschi vetusti”, eventualmente con il supporto di commissioni tecnico-scientifiche (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 - Riserva della Valbona (TN). Le foreste italiane sono state intensamente utilizzate per secoli. Negli ultimi decenni la pressione antropica sulle foreste è diminuita ed alcuni popolamenti hanno riacquistato elementi di naturalità (Foto: R. Motta).

Ingrandisci/Riduci

Apri nel Viewer

Il ruolo della comunità scientifica sarà quindi importante sia nel definire le foreste vetuste e sia, in accordo con quanto previsto dalle linee guida allegate al Decreto, nell’effettuare il monitoraggio di queste affinché la rete nazionale costituisca non solo una importante misura di conservazione, ma anche un supporto alla “gestione sostenibile” delle foreste e, più in generale, alle politiche ambientali e climatiche.

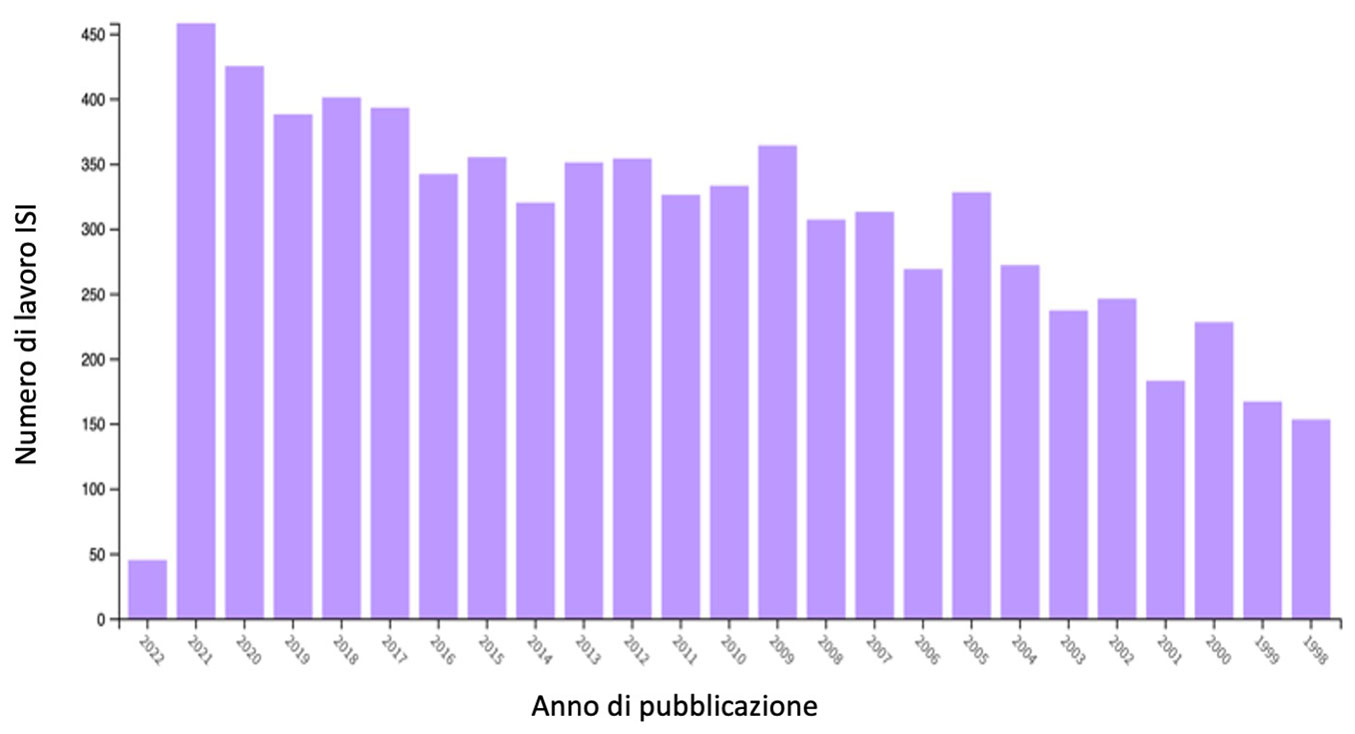

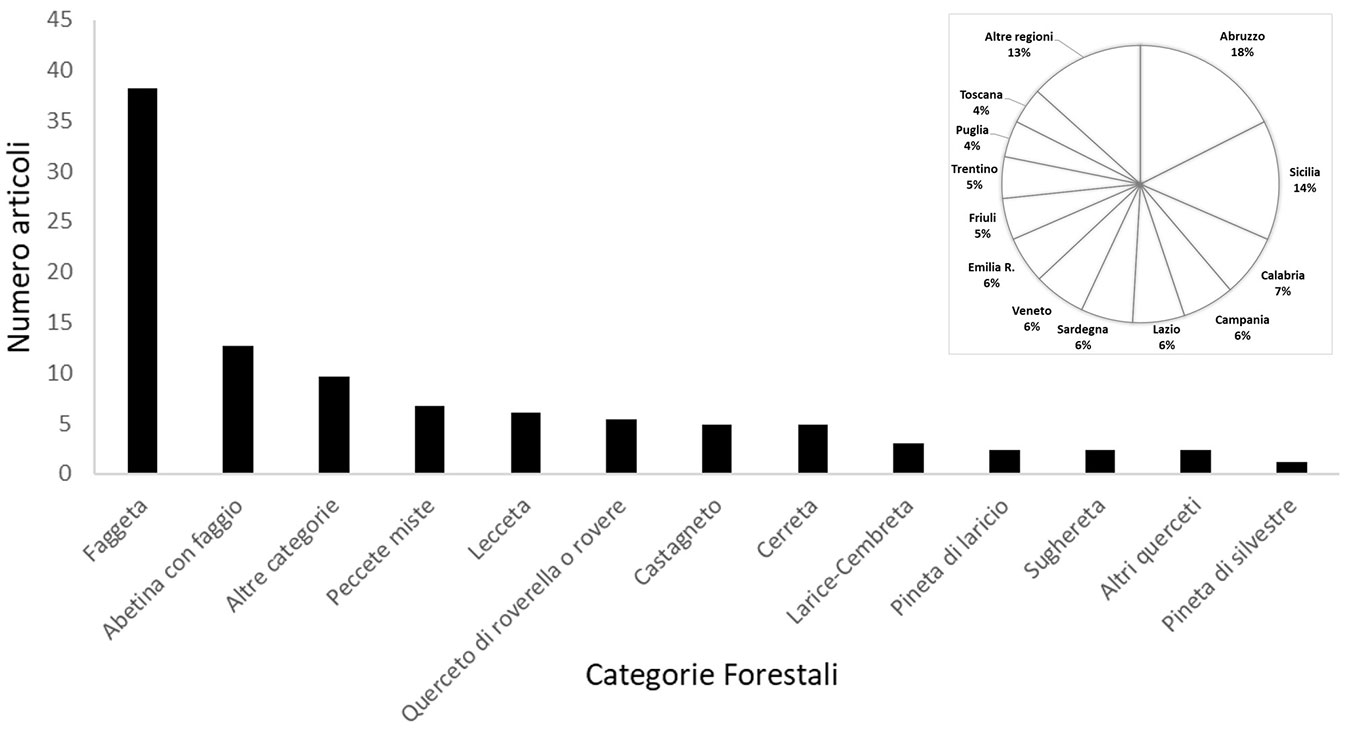

A partire dalla fine del secolo scorso le foreste vetuste sono diventate un argomento rilevante nelle ricerche del settore ecologico forestale al quale è corrisposto anche un aumento significativo dei prodotti della ricerca (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 - Lavori ISI di autori o co-autori italiani caratterizzati dallo studio di old-growth forests dal 1996 al 2021.

Ingrandisci/Riduci

Apri nel Viewer

Anche in Italia l’interesse nei confronti delle foreste vetuste è cresciuto di pari passo, sia indirizzato all’analisi dello stato attuale delle foreste italiane e all’individuazione di stadi di vetustà al loro interno, sia con la partecipazione di ricercatori italiani a progetti internazionali. Il contributo sull’argomento da parte dei nostri ricercatori si attesta come uno dei più rilevanti a livello europeo. In questo contributo viene presentato lo stato dell’arte della ricerca italiana sulle foreste vetuste, attraverso l’analisi delle pubblicazioni dei ricercatori italiani sulle foreste vetuste in Italia e all’estero, e vengono discusse le opportunità future e gli ambiti che necessitano di ulteriori approfondimenti. Per fare questo sono stati esaminati i lavori ISI-Scopus di ricercatori italiani (188 lavori iniziando dal 1996 e fino alla data del 31 dicembre 2021) integrati da lavori che sono stati pubblicati su riviste non indicizzate, monografie e report di progetti di ricerca (72 lavori individuati sempre con riferimento temporale 31 dicembre 2021). Questi lavori sono stati analizzati per distribuzione geografica, categoria forestale, tipologia di dati raccolti (quantitativi e qualitativi) con particolare attenzione a tre elementi: (i) analisi strutturale; (ii) utilizzo di bioindicatori per il confronto tra popolamenti vetusti e boschi coltivati; (iii) confronto tra popolamenti italiani e popolamenti di riferimento dell’Europa centro-orientale caratterizzati da elevato livello di vetustà.

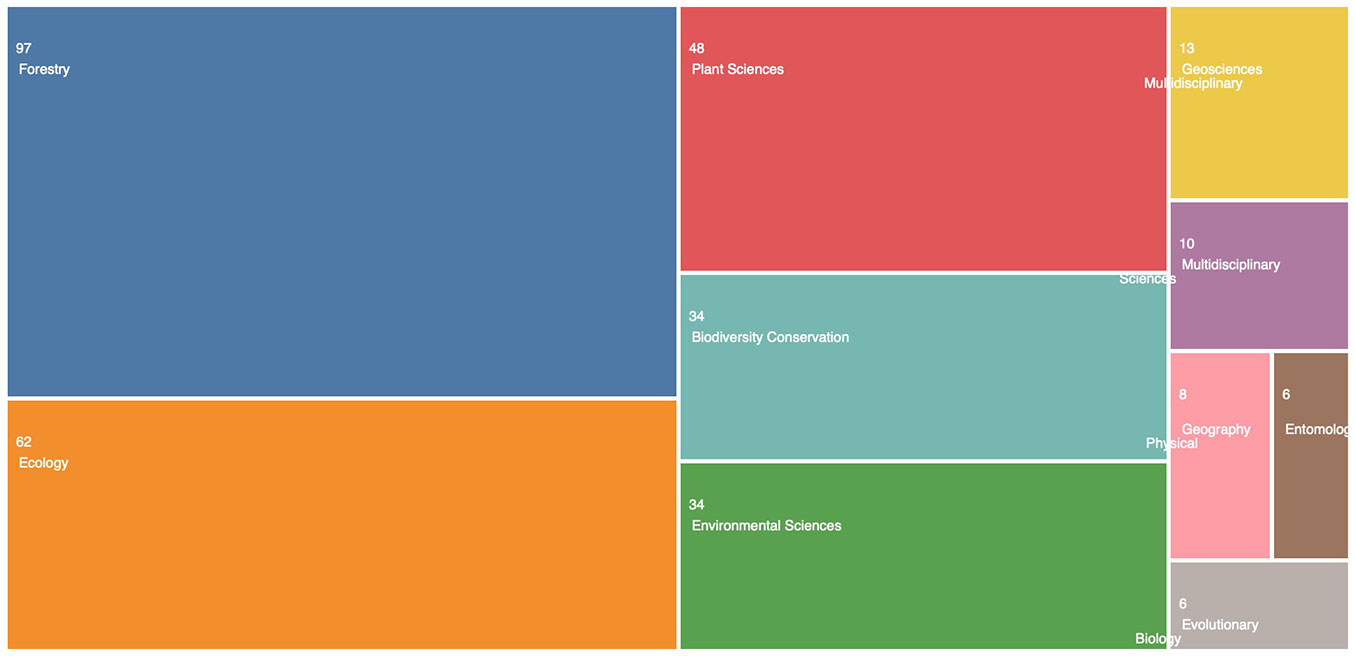

Tra i settori di ricerca (secondo le Web of Science categories - Fig. 3) prevalgono gli studi legati alle scienze forestali e all’ecologia forestale, ma emerge una buona rappresentatività di studi legati alla scienza della vegetazione ed allo studio e conservazione della biodiversità.

Fig. 3 - Settori di ricerca ISI per gli studi su foreste vetuste fatti da ricercatori italiani.

Ingrandisci/Riduci

Apri nel Viewer

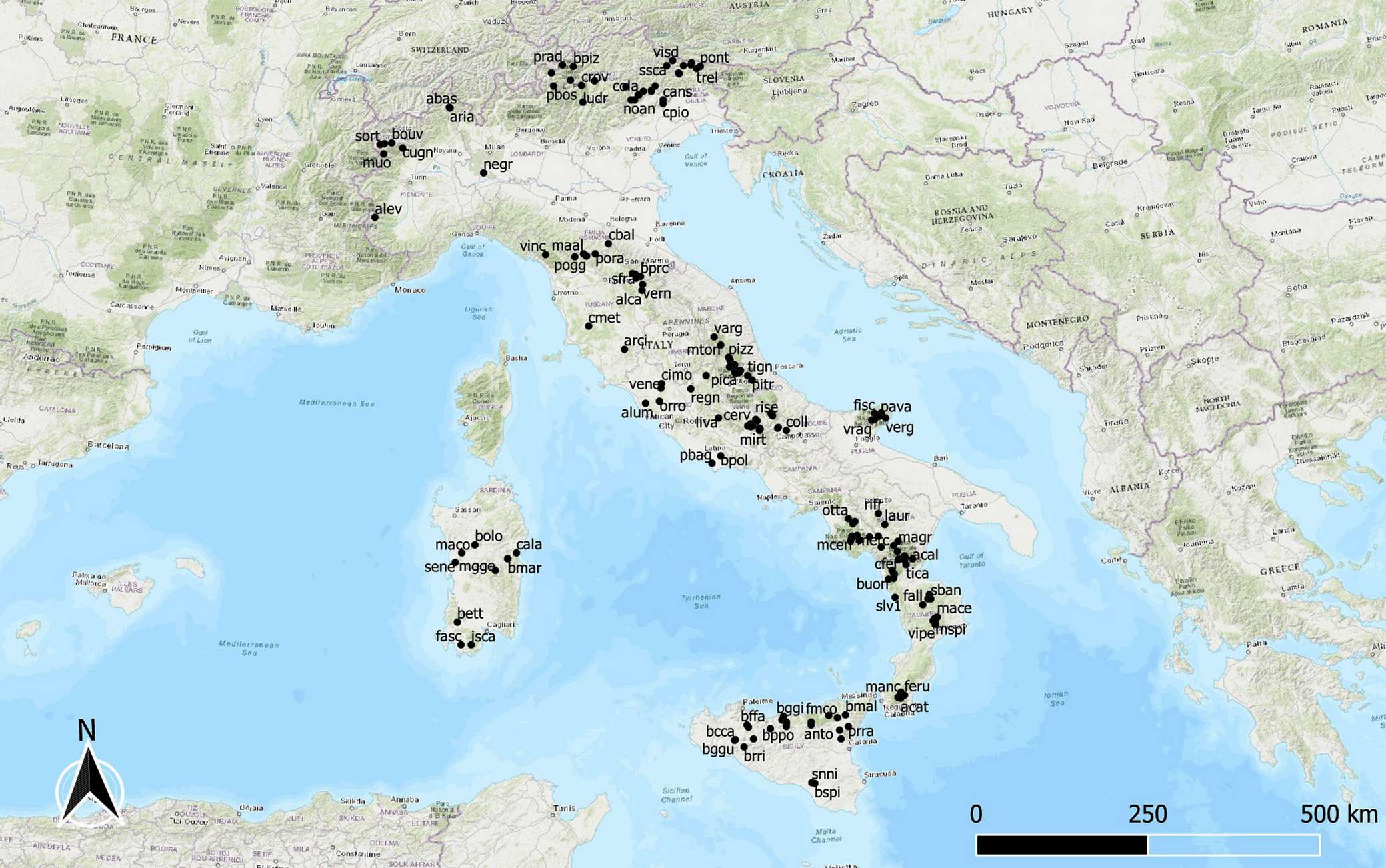

Analisi della distribuzione geografica dei siti italiani

Dall’analisi della letteratura è stato possibile mappare 165 siti oggetto di studio (Fig. 4). I siti individuati includono sia popolamenti che hanno oggettivamente caratteristiche di foreste vetuste (dal punto di vista scientifico e dal punto di vista dei requisiti richiesti dal Decreto), sia popolamenti che hanno una limitata ma significativa presenza di caratteristiche strutturali e/o indicatori biologici di vetustà, ma anche popolamenti che sono stati definiti vetusti dagli autori senza riferimenti a caratteristiche strutturali e/o a condizioni di pregressa assenza di disturbi e che non hanno i requisiti indicati dal decreto istitutivo dell’Albo.

Fig. 4 - Distribuzione geografica dei siti individuati nella letteratura esaminata come foreste recanti caratteri di vetustà.

Ingrandisci/Riduci

Apri nel Viewer

Da un punto di vista geografico il 54% dei siti si trova nell’Italia meridionale, il 28% al nord, il 13% al centro e l’8% nelle isole. Le regioni Abruzzo e Sicilia registrano il maggior numero di siti (29 e 23 rispettivamente); l’Umbria e la Liguria non hanno evidenziato siti oggetto di ricerche sulle foreste vetuste (Fig. 5). I boschi a dominanza di faggio risultano i maggiormente rappresentati (38%), seguiti dalle abetine con e senza faggio (13%) e dalle peccete (7%). Alcune categorie forestali sono invece poco rappresentate o del tutto assenti (ad es., i querceti ed i boschi di latifoglie). Faggete ed abetine pur rappresentando circa il 21% delle foreste italiane (in termini di volume - dati INFC 2015) sono oggetto di oltre il 50% delle ricerche sulle foreste vetuste rappresentando quindi la categoria forestale di gran lunga più importante e rappresentata a livello nazionale.

Fig. 5 - Categorie forestali maggiormente rappresentate dall’analisi bibliografica sulle foreste vetuste. Nell’inserto in alto a destra viene riportato un grafico recante l’importanza percentuale delle diverse regioni italiane.

Ingrandisci/Riduci

Apri nel Viewer

Analisi strutturale

La caratterizzazione delle foreste vetuste attraverso parametri strutturali risulta essere un comune denominatore nella maggior parte delle ricerche condotte sull’argomento e circa il 60% dei lavori ha descritto e/o utilizzato caratteri strutturali. Meno della metà di questi lavori ha però raccolto dati quantitativi dei parametri strutturali utilizzati. Con il termine struttura forestale si fa riferimento alla modalità con la quale le diverse parti di un popolamento si distribuiscono nello spazio, nel tempo o si organizzano funzionalmente. L’analisi strutturale è particolarmente importante in quanto una foresta vetusta presenta caratteristiche strutturali peculiari che la differenziano dai popolamenti forestali gestiti e/o più giovani. Definizioni basate unicamente sugli attributi strutturali, in ogni caso, non tengono conto della variabilità dei tipi forestali, caratteristica delle foreste italiane. I tipi forestali, oltre ai fattori climatici, disturbi naturali, e caratteristiche stazionali, possono infatti influenzare l’età alla quale una foresta diventa vetusta e quindi sviluppa i relativi attributi strutturali.

Dall’analisi svolta emerge che i principali elementi relativi alla struttura forestale considerati nella valutazione e caratterizzazione della vetustà di popolamenti forestali in Italia e in ambiti biogeografici comparabili sono riconducibili principalmente alle seguenti componenti:

- dimensione delle piante;

- distribuzione verticale e orizzontale;

- area basimetrica e volume;

- distribuzione spaziale degli alberi e delle aperture (gap).

La dimensione temporale ha un ruolo rilevante nello sviluppo delle caratteristiche strutturali di vetustà in quanto i principali elementi strutturali necessitano di un certo numero di anni per potersi manifestare, sia in riferimento all’ultimo disturbo naturale o antropico che si è manifestato (meno del 10% dei lavori cita questo dato), sia in riferimento all’età degli alberi (meno del 20% dei lavori esamina l’età degli alberi per la costruzione della struttura dell’età o almeno l’età degli alberi dominanti o più vecchi). Il decreto fa riferimento ad un tempo minimo di 60 anni in assenza di disturbi [2]. Tale periodo deve essere sufficientemente lungo da permettere alle dinamiche naturali di manifestarsi, consentendo al sistema di accumulare necromassa (legata sia a processi di competizione endogeni e sia a disturbi su piccola scala provocati da fattori esogeni) e agli alberi di raggiungere dimensioni ed età prossimi ai valori massimi delle specie. In tal senso, l’uso di indicatori è sicuramente d’aiuto per caratterizzare il grado di vetustà e misurarne lo stadio di sviluppo. La necromassa è quindi universalmente utilizzata come un importante indicatore di vetustà ed è un fattore analizzato, qualitativamente e quantitativamente, dal 24% dei lavori esaminati. Nonostante l’importanza di questo parametro, l’analisi quantitativa è limitata al 16% dei lavori. A titolo esemplificativo, il rapporto tra necromassa e biomassa viva nelle foreste italiane studiate varia tra il 10 ed il 20%, mentre questo rapporto raggiunge valori molto più elevati (30-50%) nelle foreste vetuste primarie e secondarie della penisola balcanica.

L’invecchiamento degli alberi e la mortalità, soprattutto di esemplari del piano dominante, aumenta anche la quantità di microhabitat (analizzati solo dal 4% dei lavori), che favoriscono la presenza di specie animali e vegetali tipiche delle fasi mature e stramature. Infine, le foreste vetuste sono tendenzialmente caratterizzate da un’elevata eterogeneità spaziale (esaminata dal 9% dei lavori), che si può esprimere a scale spazio-temporali differenti.

Analisi degli indicatori biologici

Le foreste vetuste, nella loro complessità strutturale, rappresentano un habitat di nicchia per numerose specie che sono tipiche, e a volte esclusive, delle fasi più mature della dinamica forestale. La presenza di queste specie è legata a caratteristiche strutturali tra le quali le più importanti sono la presenza dei microhabitat e la quantità e la qualità della necromassa che ospita specie saproxiliche. Molte caratteristiche strutturali contribuiscono a favorire la presenza di taxa che possono essere utilizzati come indicatori biologici del grado di vetustà di un popolamento forestale. Nel complesso oltre il 40% dei lavori analizzati fa riferimento all’importante ruolo della biodiversità nelle foreste vetuste mentre lo studio e l’utilizzo di indicatori biologici ha riguardato il 32% dei lavori esaminati.

Dalla letteratura scientifica italiana è emerso che gli insetti saproxilici siano stati utilizzati nel 13% dei lavori, in linea con la letteratura internazionale che privilegia i coleotteri carabidi come indicatori biologici per valutare lo stato di conservazione delle comunità forestali.

Anche la diversità e ricchezza floristica è stata oggetto di studi in foreste vetuste con particolare attenzione alla diversità lichenica (il 13% dei lavori esaminati) anche per il confronto tra queste e popolamenti intensamente utilizzati. L’uso di tali indicatori richiede il contributo di esperti e la combinazione con altri indicatori legati alla quantificazione delle specie indicatrici di vetustà dei popolamenti.

Analisi e confronti tra foreste vetuste e foreste gestite e tra foreste italiane con elementi di vetustà e foreste vetuste europee

Uno degli errori più frequenti che riguardano la definizione di “foreste vetuste” è quello di confondere le foreste vetuste con le foreste primarie o foreste vergini. Esistono decine di definizioni di foreste vetuste che quasi sempre partono dai parametri strutturali ma che spesso, anche per l’oggettiva difficoltà legata all’eterogeneità delle caratteristiche strutturali e stazionali, non tengono conto di un elemento di fondamentale importanza e cioè che una foresta vetusta non è definibile di per sé se non è collocata all’interno di un processo o gradiente di “dinamica forestale”. Le foreste vetuste rappresentano infatti uno “stadio” della dinamica forestale che, come tutti gli stadi, è comunque transitorio, e può permanere per un periodo di tempo più o meno lungo in funzione del tipo di bioma, ecosistema e regime di disturbi naturali. Le caratteristiche strutturali dello stadio di vetustà si possono sviluppare durante lunghi periodi di tempo in cui non si verificano disturbi sia di carattere naturale che di carattere antropico ed è quindi evidente che esistono foreste primarie che non sono foreste vetuste perché si trovano in uno stadio del processo dinamico precoce (ad esempio la fase di ricolonizzazione dopo un disturbo naturale) ed al contrario esistono foreste vetuste (e tutti i lembi di foresta vetusta presenti in Europa occidentale ne sono un esempio) che nel passato oltre a disturbi naturali hanno subito disturbi antropici (ad es., tagli o uso pascolivo) ma che dopo questi disturbi, se questi non sono stati così intensi da uscire dal range naturale di variabilità, hanno avuto un tempo sufficiente per sviluppare le caratteristiche strutturali tipiche dello stadio di vetustà.

A questo proposito è molto esplicativa la definizione di foresta vetusta della FAO e della Convenzione sulla Diversità biologica (⇒ https://www.cbd.int/forest/definitions.shtml): “le foreste vetuste sono popolamenti primari o secondari che hanno sviluppato una composizione ed una struttura tipica delle fasi più mature delle foreste primarie in modo da potere essere qualitativamente e quantitativamente distinto da ogni popolamento di età più giovane”. Secondo questa definizione, quindi, non è importante se la foresta è primaria o secondaria né la struttura del popolamento analizzata di per sé, ma il fattore discriminante è la “differenza significativa” della struttura e della composizione rispetto agli stadi giovanili ed alle foreste coltivate.

Per questo motivo le foreste vetuste sono di fondamentale importanza in quanto rappresentano un riferimento per le foreste coltivate e costituiscono dei modelli (sia dal punto di vista dei processi in atto e sia dal punto di vista della eterogeneità strutturale). Ai fini dell’applicazione di una selvicoltura che imita i processi naturali è utile misurare la “differenza” tra foreste vetuste (foreste attualmente nello stadio di vetustà), foreste non più gestite con elementi di vetustà e foreste attualmente coltivate.

L’uso delle foreste vetuste come riferimento per la gestione sostenibile delle foreste coltivate è stato preso in considerazione nel 29% dei lavori esaminati sia negli aspetti strutturali e dinamici e sia nell’analisi di presenza di bioindicatori.

In un territorio come quello italiano, che è stato caratterizzato nel passato da un uso intenso di tutti i popolamenti forestali e dove la gestione forestale attuata per secoli ha mantenuto i popolamenti forestali in stadi relativamente giovani, impedendo di fatto un naturale invecchiamento dei boschi con conseguente scomparsa dei popolamenti più maturi, è però altrettanto importante valutare la “quantità di vetustà” che è presente nelle nostre foreste, anche quelle che hanno potuto svilupparsi in assenza di disturbi naturali ed antropici per un lungo periodo di tempo, in confronto a popolamenti vetusti che hanno un grado di conservazione migliore e che sono assenti in Italia. Questi popolamenti, per affinità stazionali e vegetazionali, si trovano soprattutto nell’Europa orientale dove, nonostante non sia possibile trovare territori in cui la presenza dell’uomo non abbia avuto influenze in tempi antichi, le vicende storiche e socio-economiche, la posizione geografica decentrata e le ridotte densità di popolazione hanno permesso la conservazione di alcuni lembi di foresta vetusta che possono essere considerati dei modelli di riferimento di “vetustà” (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 - La foresta di Lom (Bosnia-Erzegovina). Nella fascia delle foreste temperate europee restano pochi lembi di foresta che rappresentano la massima espressione dello stadio di vetustà. Le Alpi Dinariche ed i Carpazi ospitano i riferimenti più prossimi ed adeguati per i tipi forestali presenti in Italia (Foto: R. Motta).

Ingrandisci/Riduci

Apri nel Viewer

I lavori esaminati che si sono occupati del confronto tra popolamenti vetusti italiani (popolamenti che rappresentano l’attuale massimo stadio di invecchiamento in Italia) e popolamenti di riferimento dell’Europa centro-orientale sono stati relativamente pochi (4%).

Discussione

Negli ultimi 24 anni la ricerca sulle foreste vetuste, in Italia e da parte di ricercatori italiani, ha visto un notevole aumento di interesse e la pubblicazione di numerosi prodotti di ricerca.

I popolamenti italiani oggetto di studio nell’ambito di ricerche che hanno riguardato “popolamenti vetusti” sono stati numerosi (n = 165 dei quali è stato possibile definire le coordinate).

Da un punto di vista della distribuzione territoriale e da un punto di vista della distribuzione tra le categorie forestali, come peraltro ci si poteva aspettare, non c’è una distribuzione uniforme. Per quanto riguarda la distribuzione territoriale esistono aree che sono particolarmente ricche, per ragioni storiche, ambientali e socio-economiche, di foreste che hanno caratteristiche di vetustà (ad esempio l’Abruzzo), ma anche regioni dove non sono state svolte ricerche specifiche per l’assenza di foreste vetuste oppure per mancanza di attenzione da parte dei diversi gruppi di ricerca. Per quanto riguarda le categorie forestali, le faggete, con o senza abete bianco, sono state le foreste di gran lunga più studiate.

Per quanto concerne l’utilizzo dei parametri strutturali quali elementi diagnostici per l’individuazione dello stadio di vetustà all’interno dei popolamenti forestali italiani, i lavori che hanno utilizzato parametri o indicatori quantitativi per giustificare la definizione di vetustà sono un numero relativamente limitato, sia per quanto riguarda gli alberi vivi, sia per quanto riguarda la necromassa. Sulla base dell’analisi dei dati disponibili emerge che una buona parte di questi popolamenti non rientra nei criteri stabiliti dal Decreto istitutivo dell’Albo delle foreste vetuste e che l’utilizzo del termine vetusto da parte degli autori non è sempre stato rigoroso e giustificato.

Per quanto riguarda gli indicatori biologici utilizzati, il numero di ricerche che ha interessato licheni ed insetti saproxilici è relativamente elevato, anche se spesso manca un’indicazione strutturale quantitativa che permetterebbe di individuare delle soglie di vetustà (ad esempio il volume della necromassa). Gli indicatori biologici hanno un ruolo molto importante nell’individuare le “soglie” di caratteristiche strutturali di vetustà che sono necessarie per identificare le vere foreste vetuste, le foreste vetuste potenziali ed anche per dare indicazioni sul rilascio di alberi vivi e morti da mantenere nelle foreste coltivate. È quindi auspicabile una maggiore diffusione degli studi sugli indicatori biologici ed una maggiore collaborazione e sinergia tra questi studi e l’applicazione di criteri di gestione forestale sostenibile. Lo studio del ruolo degli “alberi habitat”, sia all’interno delle foreste vetuste che nell’ambito di popolamenti coltivati, è stato avviato solamente in tempi recenti, ma anche in questo caso l’aumento della massa critica delle ricerche potrebbe permettere di individuare una serie di “indicatori di vetustà” che possano contribuire a definire le priorità di inserimento nell’Albo delle foreste candidate, nonché individuare foreste che attualmente non hanno i requisiti ma che potrebbero potenzialmente acquisirli nei prossimi decenni. Nello stesso tempo questa massa critica di informazioni potrebbe anche permettere di individuare elementi e/o caratteristiche che potrebbero essere inseriti/conservati/favoriti nelle foreste coltivate.

Uno degli ambiti di ricerca maggiormente sviluppati è il confronto di popolamenti giovani e coltivati con popolamenti che sono attualmente considerati vetusti o che rappresentano l’attuale massimo stadio di vetustà in Italia. Al contrario, i lavori che hanno effettuato confronti tra foreste italiane con elementi di vetustà e “veri” popolamenti vetusti dell’Europa centro-orientale sono relativamente pochi, ed anche in questo caso limitati a poche categorie forestali (anche se foreste vetuste non sono attualmente disponibili in Europa per tutte le categorie forestali).

Tra i settori di ricerca che sono stati solo recentemente valorizzati nelle ricerche sulle foreste vetuste, ma che avranno grandi potenzialità nei prossimi anni, ci sono sicuramente lo studio dei processi fisiologici e dei cicli degli elementi, in quanto le foreste vetuste rappresentano un riferimento importante per lo studio dell’impatto del cambiamento climatico sui popolamenti forestali (essendo assente o limitato il “rumore” dovuto all’azione antropica). Al momento queste ricerche riguardano meno del 10% dei lavori esaminati, ma sono state in forte crescita negli ultimi 5 anni. Per tale motivo, è auspicabile che l’istituzione della rete di foreste vetuste sia abbinata (come prevedono le Linee guida allegate al Decreto) ad una rete di monitoraggio e osservazione permanente che possa svolgere una funzione importante come riferimento per la gestione naturalistica delle foreste e per lo studio dell’impatto del cambiamento climatico.

In conclusione, lo stato attuale della ricerca in Italia sulle foreste vetuste permette già ora di avere una serie di conoscenze che possono essere utilizzate per la realizzazione di una rete nazionale adeguata sia agli scopi di conservazione che agli scopi di ricerca e supporto alla gestione sostenibile delle risorse naturali, integrando attributi e aree di vetustà in foreste multifunzionali. È opportuno che i ricercatori siano coinvolti sia in sede di individuazione e riconoscimento delle foreste vetuste che nella fase successiva di monitoraggio e conservazione degli attributi di vetustà. Per ottimizzare non solo il ruolo di conservazione ma anche quello di ricerca e supporto alla gestione delle risorse naturali, sarebbe auspicabile sviluppare un protocollo di monitoraggio comune a tutte le foreste inserite nell’Albo o perlomeno ad una quota significativa e rappresentativa, con il coordinamento del DIFOR e la collaborazione delle Regioni e delle Province autonome, che permetterebbe confronti, analisi di lungo periodo ed anche l’inserimento di questa rete in importanti infrastrutture di ricerca come la rete LTER (⇒ http://www.lteritalia.it/).

La costituenda Rete nazionale dei boschi vetusti potrebbe quindi rappresentare un’importante infrastruttura di ricerca, favorire lo sviluppo di collaborazioni interdisciplinari, sviluppare argomenti e settori di ricerca che ad oggi non sono stati adeguatamente presidiati.

Infine, la rete potrebbe essere un’ulteriore occasione di collaborazione tra amministrazioni, gestori delle risorse naturali e ricercatori in modo da raggiungere gli obiettivi previsti dalle strategie sulla biodiversità e sulle foreste italiane e della UE, quali la rigorosa protezione delle foreste vetuste e una migliore gestione sostenibile delle foreste e delle risorse naturali applicando un closer to nature forest management come previsto dalle Strategie biodiversità e foreste della UE.

Bibliografia Citata

(1)

Achard F, Eva H, Mollicone D, Popatov P, Stibig HJ, Turubanova S, Yaroshenko A (2009). Detecting intact forests from space: hot spots of loss, deforestation and the UNFCCC. In: “Old-Growth Forests” (Wirth C, Gleixner G, Heimann M eds). Ecological Studies, vol. 207, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 411-427.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(2)

Alessandrini A, Biondi F, Di Filippo A, Ziaco E, Piovesan G (2011). Tree size distribution at increasing spatial scales converges to the rotated sigmoid curve in two old-growth beech stands of the Italian Apennines. Forest Ecology and Management 262: 1950-62.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(3)

Amori G, Mazzei A, Storino P, Urso S, Luzzi G, Aloise G, Gangale C, Ouzounov D, Luiselli L, Pizzolotto R, Brandmayr P (2021). Forest management and conservation of faunal diversity in Italy: a review. Plant Biosystems 155: 1226-39.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(4)

Anfodillo T, Carrer M, Simini F, Popa I, Banavar JR, Maritan A (2013). An allometry-based approach for understanding forest structure, predicting tree-size distribution and assessing the degree of disturbance. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 280 (1751): 20122375.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(5)

Badalamenti E, Battipaglia G, Gristina L, Novara A, Ruhl J, Sala G, Sapienza L, Valentini R, La Mantia T (2019). Carbon stock increases up to old growth forest along a secondary succession in Mediterranean island ecosystems. PLoS One 14 (7): e0220194.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(6)

Badalamenti E, La Mantia T, La Mantia G, Cairone A, La Mela Veca DS (2017). Living and dead aboveground biomass in Mediterranean forests: evidence of old-growth traits in a Quercus pubescens Willd. s. l. Stand. Forests 8 (6): 187.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(7)

Balestrieri R, Basile M, Posillico M, Altea T, De Cinti B, Matteucci G (2015). A guild-based approach to assessing the influence of beech forest structure on bird communities. Forest Ecology and Management 356: 216-23.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(8)

Barbati A, Salvati R, Ferrari B, Di Santo D, Quatrini A, Portoghesi L, Travaglini D, Iovino F, Nocentini S (2012). Assessing and promoting old-growthness of forest stands: lessons from research in Italy. Plant Biosystems 146: 167-174.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(9)

Barbati A, Marchetti M, Chirici G, Corona P (2014). European Forest Types and Forest Europe SFM indicators: tools for monitoring progress on forest biodiversity conservation. Forest Ecology and Management 321: 145-57.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(10)

Barbato D, Benocci A, Manganelli G (2020). Does forest age affect soil biodiversity? Case study of land snails in Mediterranean secondary forests. Forest Ecology and Management 455: 117693.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(11)

Bartha S, Canullo R, Chelli S, Campetella G (2020). Unimodal relationships of understory alpha and beta diversity along chronosequence in coppiced and unmanaged beech forests. Diversity 12 (3): 101.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(12)

Bayat AT, Van Gils H, Weir M (2012). Carbon stock of European beech forest; a case at M. Pizzalto, Italy. Paper presented at at the “International Conference On Environmental Science and Development” (ICESD 2012). APCBEE Procedia 1: 159-168

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(13)

Behjou FK, Lo Monaco A, Tavankar F, Venanzi R, Nikooy M, Mederski PS, Picchio R (2018). Coarse woody debris variability due to human accessibility to forest. Forests 9 (9): 509.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(14)

Bernardini V, Avolio S, Plutino M (2020). Pinus nigra JF Arnold subsp. calabrica (Poir.) of the Fallistro Biogenetic Natural Reserve: state of “Giant pines” stand after 40 years of observations. Forest Systems 29.

Online |

Google Scholar

(15)

Bianchi L, Bottacci A, Calamini G, Maltoni A, Mariotti B, Quilghini G, Salbitano F, Tani A, Zoccola A, Paci M (2011). Structure and dynamics of a beech forest in a fully protected area in the northern Apennines (Sasso Fratino, Italy). iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 4: 136-144.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(16)

Blasi C, Marchetti M, Chiavetta U, Aleffi M, Audisio P, Azzella MM, Brunialti G, Capotorti G, Del Vico E, Lattanzi E, Persiani AM, Ravera S, Tilia A, Burrascano S (2010). Multi-taxon and forest structure sampling for identification of indicators and monitoring of old-growth forest. Plant Biosystems 144: 160-170.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(17)

Blasi S, Menta C, Balducci L, Conti FD, Petrini E, Piovesan G (2013). Soil microarthropod communities from Mediterranean forest ecosystems in Central Italy under different disturbances. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 185: 1637-1655.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(18)

Bonacci T, Mazzei A, Horak J, Brandmayr P (2012). Cucujus tulliae sp n. - an endemic Mediterranean saproxylic beetle from genus Cucujus Fabricius, 1775 (Coleoptera, Cucujidae), and keys for identification of adults and larvae native to Europe. ZooKeys 212: 63-79.

Online |

Google Scholar

(19)

Bonanomi G, Incerti G, Abd El-Gawad AM, Sarker TC, Stinca A, Motti R, Cesarano G, Teobaldelli M, Saulino L, Cona F, Chirico GB, Mazzoleni S, Saracino A (2018). Windstorm disturbance triggers multiple species invasion in an urban Mediterranean forest. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 11: 64-71.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(20)

Bottalico F, Travaglini D, Fiorentini S, Lisa C, Nocentini S (2014). Stand dynamics and natural regeneration in silver fir (Abies alba Mill.) plantations after traditional rotation age. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 7: 313-23.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(21)

Bottazzi P, Cattaneo A, Rocha DC, Rist S (2013). Assessing sustainable forest management under REDD plus: a community-based labour perspective. Ecological Economics 93: 94-103.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(22)

Bottero A, Garbarino M, Dukic V, Govedar Z, Lingua E, Nagel TA, Motta R (2011). Gap-phase dynamics in the old-growth forest of Lom, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Silva Fennica 45: 875-87.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(23)

Brasier CM, Vettraino AM, Chang TT, Vannini A (2010). Phytophthora lateralis discovered in an old growth Chamaecyparis forest in Taiwan. Plant Pathology 59: 595-603.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(24)

Brunialti G, Frati L, Aleffi M, Marignani M, Rosati L, Burrascano S, Ravera S (2010). Lichens and bryophytes as indicators of old-growth features in Mediterranean forests. Plant Biosystems 144: 221-33.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(25)

Brunialti G, Ravera S, Frati L (2013). Mediterranean old-growth forests: the role of forest type in the conservation of epiphytic lichens. Nova Hedwigia 96: 367-81.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(26)

Brunialti G, Frati L, Ravera S (2015). Structural variables drive the distribution of the sensitive lichen Lobaria pulmonaria in Mediterranean old-growth forests. Ecological Indicators 53: 37-42.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(27)

Brunialti G, Frati L, Calderisi M, Giorgolo F, Bagella S, Bertini G, Chianucci F, Fratini R, Gottardini E, Cutini A (2020a). Epiphytic lichen diversity and sustainable forest management criteria and indicators: a multivariate and modelling approach in coppice forests of Italy. Ecological Indicators 115 (3): 106358.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(28)

Brunialti G, Giordani P, Ravera S, Frati L (2020b). The reproductive strategy as an important trait for the distribution of lower-trunk epiphytic lichens in old-growth

vs. non-old growth forests. Forests 12 (1): 27.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(29)

Buffa G, Villani M (2012). Are the ancient forests of the Eastern Po Plain large enough for a long term conservation of herbaceous nemoral species? Plant Biosystems 146: 970-984.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(30)

Burrascano S (2010). On the terms used to refer to “natural” forests: a response to Veen et al. Biodiversity and Conservation 19: 3301-05.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(31)

Burrascano S, Chytry M, Kuemmerle T, Giarrizzo E, Luyssaert S, Sabatini FM, Blasi C (2016). Current European policies are unlikely to jointly foster carbon sequestration and protect biodiversity. Biological Conservation 201: 370-376.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(32)

Burrascano S, Keeton WS, Sabatini FM, Blasi C (2013). Commonality and variability in the structural attributes of moist temperate old-growth forests: a global review. Forest Ecology and Management 291: 458-479.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(33)

Burrascano S, Lombardi F, Marchetti M (2008). Old-growth forest structure and deadwood: Are they indicators of plant species composition? A case study from central Italy. Plant Biosystems 142: 313-323.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(34)

Burrascano S, Rosati L, Blasi C (2009). Plant species diversity in Mediterranean old-growth forests: a case study from central Italy. Plant Biosystems 143: 190-200.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(35)

Burrascano S, Sabatini FM, Blasi C (2011). Testing indicators of sustainable forest management on understorey composition and diversity in southern Italy through variation partitioning. Plant Ecology 212: 829-41.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(36)

Burrascano S, Ripullone F, Bernardo L, Borghetti M, Carli E, Colangelo M, Gangale C, Gargano D, Gentilesca T, Luzzi G, Passalacqua N, Pelle L, Rivelli AR, Sabatini FM, Schettino A, Siclari A, Uzunov D, Blasi C (2018). It’s a long way to the top: plant species diversity in the transition from managed to old-growth forests. Journal of Vegetation Science 29: 98-109.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(37)

Cagliero E, Morresi D, Paradis L, Curovic M, Spalevic V, Marchi N, Meloni F, Bentaleb I, Motta R, Garbarino M, Lingua E, Finsinger W (2022). Legacies of past human activities on one of the largest old-growth forests in the south-east European mountains. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 27: 199.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(38)

Campetella G, Chelli S, Simonetti E, Damiani C, Bartha S, Wellstein C, Giorgini D, Puletti N, Mucina L, Cervellini M, Canullo R (2020). Plant functional traits are correlated with species persistence in the herb layer of old-growth beech forests. Scientific Reports 10 (1): 1.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(39)

Capotorti G, Zavattero L, Anzellotti I, Burrascano S, Frondoni R, Marchetti M, Marignani M, Smiraglia D, Blasi C (2012). Do National Parks play an active role in conserving the natural capital of Italy? Plant Biosystems 146: 258-65.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(40)

Carpaneto GM, Chiari S, Audisio PA, Leo P, Liberto A, Jansson N, Zauli A (2013). Biological and distributional overview of the genus Eledonoprius (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae): Rare fungus-feeding beetles of European old-growth forests. European Journal of Entomology 110: 173-176.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(41)

Carrer M, Castagneri D, Popa I, Pividori M, Lingua E (2018). Tree spatial patterns and stand attributes in temperate forests: The importance of plot size, sampling design, and null model. Forest Ecology and Management 407: 125-134.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(42)

Castagneri D, Garbarino M, Berretti R, Motta R (2010a). Site and stand effects on coarse woody debris in montane mixed forests of Eastern Italian Alps. Forest Ecology and Management 260: 1592-1598.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(43)

Castagneri D, Lingua E, Vacchiano G, Nola P, Motta R (2010b). Diachronic analysis of individual-tree mortality in a Norway spruce stand in the eastern Italian Alps. Annals of Forest Science 67 (3): 304-304.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(44)

Castagneri D, Storaunet KO, Rolstad J (2013). Age and growth patterns of old Norway spruce trees in Trillemarka forest, Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 28: 232-240.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(45)

Castagneri D, Nola P, Motta R, Carrer M (2014). Summer climate variability over the last 250 years differently affected tree species radial growth in a mesic Fagus-Abies-Picea old-growth forest. Forest Ecology and Management 320: 21-29.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(46)

Casula P, Fantini S, Fenu G, Fois M, Calvia G, Bacchetta G (2021). Positive interactions between great longhorn beetles and forest structure. Forest Ecology and Management 486 (3): 118981.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(47)

Chianucci F, Minari E, Fardusi MJ, Merlini P, Cutini A, Corona P, Mason F (2016). Relationships between overstory and understory structure and diversity in semi-natural mixed floodplain forests at Bosco Fontana (Italy). iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 9: 919-926.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(48)

Chiarucci A, Piovesan G (2020). Need for a global map of forest naturalness for a sustainable future. Conservation Biology 34: 368-372.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(49)

Chiavetta U, Sallustio L, Garfì V, Maesano M, Marchetti M (2012). Classification of the oldgrowthness of forest inventory plots with dissimilarity metrics in Italian National Parks. European Journal of Forest Research 131: 1473-1483.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(50)

Chirici G, Puletti N, Salvati R, Arbi F, Zolli C, Corona P (2014). Is randomized branch sampling suitable to assess wood volume of temperate broadleaved old-growth forests? Forest Ecology and Management 312: 225-30.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(51)

Colangelo M, Camarero JJ, Gazol A, Piovesan G, Borghetti M, Baliva M, Gentilesca T, Rita A, Schettino A, Ripullone F (2021). Mediterranean old-growth forests exhibit resistance to climate warming. Science of The Total Environment 801 (1): 149684.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(52)

Collalti A, Perugini L, Santini M, Chiti T, Nole A, Matteucci G, Valentini R (2014). A process-based model to simulate growth in forests with complex structure: Evaluation and use of 3D-CMCC Forest Ecosystem Model in a deciduous forest in Central Italy. Ecological Modelling 272: 362-378.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(53)

Corona P, Fattorini L, Franceschi S (2009). Estimating the volume of forest growing stock using auxiliary information derived from relascope or ocular assessments. Forest Ecology and Management 257: 2108-2014.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(54)

Corona P (2010). Integration of forest mapping and inventory to support forest management. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 3: 59-64.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(55)

Corona P, Blasi C, Chirici G, Facioni L, Fattorini L, Ferrari B (2010). Monitoring and assessing old-growth forest stands by plot sampling. Plant Biosystems 144: 171-179.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(56)

Cullotta S, Puzzolo V, Fresta A (2015). The southernmost beech (Fagus sylvatica) forests of Europe (Mount Etna, Italy): ecology, structural stand-type diversity and management implications. Plant Biosystems 149: 88-99.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(57)

Curovic M, Spalevic V, Sestras P, Motta R, Dan C, Garbarino M, Vitali A, Urbinati C (2020). Structural and ecological characteristics of mixed broadleaved old-growth forest (Biogradska Gora - Montenegro). Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry 44: 428-438.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(58)

Danise T, Innangi M, Curcio E, Fioretto A (2022). Covariation between plant biodiversity and soil systems in a European beech forest and a black pine plantation: the case of Mount Faito, (Campania, Southern Italy). Journal of Forestry Research 33: 239-252.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(59)

De Sanctis M, Fanelli G, Gjeta E, Mullaj A, Attorre F (2018). The forest communities of Shebenik-Jabllanice National Park (Central Albania). Phytocoenologia 48: 51-76.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(60)

De Zan LR, Bellotti F, Carpaneto GM (2014). Saproxylic beetles in three relict beech forests of central Italy: analysis of environmental parameters and implications for forest management. Forest Ecology and Management 328: 229-244.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(61)

De Zan LR, De Gasperis SR, Fiore L, Battisti C, Carpaneto GM (2017). The importance of dead wood for hole-nesting birds: a two years study in three beech forests of central Italy. Israel Journal of Ecology and Evolution 63: 19-27.

Online |

Google Scholar

(62)

Della Rocca F, Bogliani G, Milanesi P (2017). Patterns of distribution and landscape connectivity of the stag beetle in a human-dominated landscape. Nature Conservation 19: 19-37.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(63)

Di Corato L, Moretto M, Vergalli S (2018). The effects of uncertain forest conservation benefits on long-run deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Environment and Development Economics 23: 413-433.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(64)

Di Filippo A, Biondi F, Cufar K, De Luis M, Grabner M, Maugeri M, Saba EP, Schirone B, Piovesan G (2007). Bioclimatology of beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) in the Eastern Alps: spatial and altitudinal climatic signals identified through a tree-ring network. Journal of Biogeography 34: 1873-1892.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(65)

Di Filippo A, Biondi F, Maugeri M, Schirone B, Piovesan G (2012). Bioclimate and growth history affect beech lifespan in the Italian Alps and Apennines. Global Change Biology 18: 960-972.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(66)

Di Filippo A, Pederson N, Baliva M, Brunetti M, Dinella A, Kitamura K, Knapp HD, Schirone B, Piovesan G (2015). The longevity of broadleaf deciduous trees in Northern Hemisphere temperate forests: insights from tree-ring series. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 3: 347.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(67)

Di Filippo A, Biondi F, Piovesan G, Ziaco E (2017). Tree ring-based metrics for assessing old-growth forest naturalness. Journal of Applied Ecology 54: 737-749.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(68)

Fantini S, Fois M, Casula P, Fenu G, Calvia G, Bacchetta G (2020). Structural heterogeneity and old-growthness: a first regional-scale assessment of Sardinian forests. Annals of Forest Research 63: 103-120.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(69)

Farina A, Righini R, Fuller S, Li P, Pavan G (2021). Acoustic complexity indices reveal the acoustic communities of the old-growth Mediterranean forest of Sasso Fratino Integral Natural Reserve (Central Italy). Ecological Indicators 120 (1421): 106927.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(70)

Feoli E, Ganis P, Venanzoni R, Zuccarello V (2011). Toward a framework of integrated knowledge of terrestrial vegetation system: The role of databases of phytosociological releves. Plant Biosystems 145: 74-84.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(71)

Feoli E (2012). Diversity patterns of vegetation systems from the perspective of similarity theory. Plant Biosystems 146: 797-804.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(72)

Frascaroli F, Bhagwat S, Guarino R, Chiarucci A, Schmid B (2016). Shrines in Central Italy conserve plant diversity and large trees. Ambio 45: 468-79.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(73)

Frate L, Carranza ML, Garfi V, Di Febbraro M, Tonti D, Marchetti M, Ottaviano M, Santopuoli G, Chirici G (2016). Spatially explicit estimation of forest age by integrating remotely sensed data and inverse yield modeling techniques. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 9: 63-71.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(74)

Fravolini G, Egli M, Derungs C, Cherubini P, Ascher-Jenull J, Gomez-Brandon M, Bardelli T, Tognetti R, Lombardi F, Marchetti M (2016). Soil attributes and microclimate are important drivers of initial deadwood decay in sub-alpine Norway spruce forests. Science of the Total Environment 569: 1064-1076.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(75)

Fravolini G, Tognetti R, Lombardi F, Egli M, Ascher-Jenull J, Arfaioli P, Bardelli T, Cherubini P, Marchetti M (2018). Quantifying decay progression of deadwood in Mediterranean mountain forests. Forest Ecology and Management 408: 228-237.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(76)

Garbarino M, Mondino EB, Lingua E, Nagel TA, Dukic V, Govedar Z, Motta R (2012). Gap disturbances and regeneration patterns in a Bosnian old-growth forest: a multispectral remote sensing and ground-based approach. Annals of Forest Science 69: 617-625.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(77)

Garbarino M, Marzano R, Shaw JD, Long JN (2015). Environmental drivers of deadwood dynamics in woodlands and forests. Ecosphere 6 (3): art30.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(78)

Giannetti F, Puletti N, Puliti S, Travaglini D, Chirici G (2020). Assessment of UAV photogrammetric DTM-independent variables for modelling and mapping forest structural indices in mixed temperate forests. Ecological Indicators 117 (8): 106513.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(79)

Gilhen-Baker M, Roviello V, Beresford-Kroeger D, Roviello GN (2022). Old growth forests and large old trees as critical organisms connecting ecosystems and human health. A review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 20 (2): 1529-1538.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(80)

Gonmadje C, Picard N, Gourlet-Fleury S, Rejou-Mechain M, Freycon V, Sunderland T, Mckey D, Doumenge C (2017). Altitudinal filtering of large-tree species explains above-ground biomass variation in an Atlantic Central African rain forest. Journal of Tropical Ecology 33: 143-154.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(81)

Gossner MM, Gazzea E, Diedus V, Jonker M, Yaremchuk M (2020). Using sentinel prey to assess predation pressure from terrestrial predators in water-filled tree holes. European Journal of Entomology 117: 226-234.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(82)

Granata MU, Gratani L, Bracco F, Catoni R (2019). Carbon dioxide sequestration capability of an unmanaged old-growth broadleaf deciduous forest in a strict Nature Reserve. Journal of Sustainable Forestry 38: 85-96.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(83)

Granata MU, Gratani L, Bracco F, Sartori F, Catoni R (2016). Carbon stock estimation in an unmanaged old-growth forest: a case study from a broad-leaf deciduous forest in the Northwest of Italy. International Forestry Review 18: 444-451.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(84)

Granata MU, Bracco F, Catoni R (2020). Phenotypic plasticity of two invasive alien plant species inside a deciduous forest in a strict nature reserve in Italy. Journal of Sustainable Forestry 39: 346-364.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(85)

Granito VM, Lunghini D, Maggi O, Persiani AM (2015). Wood-inhabiting fungi in southern Italy forest stands: morphogroups, vegetation types and decay classes. Mycologia 107: 1074-88.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(86)

Hacket-Pain A, Ascoli D, Berretti R, Mencuccini M, Motta R, Nola P, Piussi P, Ruffinatto F, Vacchiano G (2019). Temperature and masting control Norway spruce growth, but with high individual tree variability. Forest Ecology and Management 438: 142-150.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(87)

Hahn K, Christensen M (2005). Dead wood in European forest reserves - A reference for forest management. Paper presented at the International Conference “Monitoring and Indicators of Forest Biodiversity in Europe - From Ideas To Operationality”.

Google Scholar

(88)

Hardersen S, Bardiani M, Chiari S, Maura M, Maurizi E, Roversi PF, Mason F, Bologna MA (2017). Guidelines for the monitoring of Morimus asper funereus and Morimus asper asper. Nature Conservation 20 (85-88): 205-236.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(89)

Jourgholami M, Feghhi J, Tavankar F, Latterini F, Venanzi R, Picchio R (2021). Short-term effects in canopy gap area on the recovery of compacted soil caused by forest harvesting in old-growth Oriental beech (Fagus orientalis Lipsky) stands. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 14: 370-377.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(90)

Keren S, Diaci J, Motta R, Govedar Z (2017). Stand structural complexity of mixed old-growth and adjacent selection forests in the Dinaric Mountains of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Forest Ecology and Management 400: 531-41.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(91)

Keren S, Motta R, Govedar Z, Lucic R, Medarevic M, Diaci J (2014). Comparative structural dynamics of the Janj mixed old-growth mountain forest in Bosnia and Herzegovina: are conifers in a long-term decline? Forests 5: 1243-66.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(92)

Kooch Y, Moghimian N, Alberti G (2020). C and N cycle under beech and hornbeam tree species in the Iranian old-growth forests. Catena 187 (8): 104406.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(93)

Laiolo P, Caprio E, Rolando A (2003). Effects of logging and non-native tree proliferation on the birds overwintering in the upland forests of north-western Italy. Forest Ecology and Management 179: 441-454.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(94)

Lamedica S, Lingua E, Popa I, Motta R, Carrer M (2011). Spatial structure in four Norway spruce stands with different management history in the Alps and Carpathians. Silva Fennica 45: 865-73.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(95)

Lamonaca A, Corona P, Barbati A (2008). Exploring forest structural complexity by multi-scale segmentation of VHR imagery. Remote Sensing of Environment 112: 2839-2849.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(96)

Law BE, Van Tuyl S, Cescatti A, Baldocchi DD (2001). Estimation of leaf area index in open-canopy ponderosa pine forests at different successional stages and management regimes in Oregon. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 108: 1-14.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(97)

Lelli C, Bruun HH, Chiarucci A, Donati D, Frascaroli F, Fritz O, Goldberg I, Nascimbene J, Tottrup AP, Rahbek C, Heilmann-Clausen J (2019). Biodiversity response to forest structure and management: Comparing species richness, conservation relevant species and functional diversity as metrics in forest conservation. Forest Ecology and Management 432: 707-717.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(98)

Lingua E, Garbarino M, Mondino EB, Motta R (2011). Natural disturbance dynamics in an old-growth forest: from tree to landscape. Procedia Environmental Sciences 7: 365-370.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(99)

Lo Monaco A, Luziatelli G, Latterini F, Tavankar F, Picchio R (2020). Structure and dynamics of deadwood in pine and oak stands and their role in CO

2 sequestration in lowland forests of Central Italy. Forests 11 (3): 253.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(100)

Lombardi F, Cherubini P, Lasserre B, Tognetti R, Marchetti M (2008a). Tree rings used to assess time since death of deadwood of different decay classes in beech and silver fir forests in the central Apennines (Molise, Italy). Canadian Journal of Forest Research 38: 821-833.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(101)

Lombardi F, Cocozza C, Lasserre B, Tognetti R, Marchetti M (2011). Dendrochronological assessment of the time since death of dead wood in an old growth Magellan’s beech forest, Navarino Island (Chile). Austral Ecology 36: 329-40.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(102)

Lombardi F, Klopcic M, Di Martino P, Tognetti R, Chirici G, Boncina A, Marchetti M (2012a). Comparison of forest stand structure and management of silver fir-European beech forests in the Central Apennines, Italy and in the Dinaric Mountains, Slovenia. Plant Biosystems 146: 114-123.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(103)

Lombardi F, Lasserre B, Chirici G, Tognetti R, Marchetti M (2012b). Deadwood occurrence and forest structure as indicators of old-growth forest conditions in Mediterranean mountainous ecosystems. Ecoscience 19: 344-355.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(104)

Lombardi F, Lasserre B, Tognetti R, Marchetti M (2008b). Deadwood in relation to stand management and forest type in Central Apennines (Molise, Italy). Ecosystems 11: 882-894.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(105)

Lombardi F, Marchetti M, Corona P, Merlini P, Chirici G, Tognetti R, Burrascano S, Alivernini A, Puletti N (2015). Quantifying the effect of sampling plot size on the estimation of structural indicators in old-growth forest stands. Forest Ecology and Management 346: 89-97.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(106)

Mancini MS, Galli A, Niccolucci V, Lin D, Bastianoni S, Wackernagel M, Marchettini N (2016). Ecological footprint: refining the carbon footprint calculation. Ecological Indicators 61: 390-403.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(107)

Manes F, Ricotta C, Salvatori E, Bajocco S, Blasi C (2010). A multiscale analysis of canopy structure in Fagus sylvatica L. and Quercus cerris L. old-growth forests in the Cilento and Vallo di Diano National Park. Plant Biosystems 144: 202-210.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(108)

Marchetti M, Sallustio L, Ottaviano M, Barbati A, Corona P, Tognetti R, Zavattero L, Capotorti G (2012). Carbon sequestration by forests in the National Parks of Italy. Plant Biosystems 146: 1001-11.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(109)

Marchetti M, Tognetti R, Lombardi F, Chiavetta U, Palumbo G, Sellitto M, Colombo C, Iovieno P, Alfani A, Baldantoni D, Barbati A, Ferrari B, Bonacquisti S, Capotorti G, Copiz R, Blasi C (2010). Ecological portrayal of old-growth forests and persistent woodlands in the Cilento and Vallo di Diano National Park (southern Italy). Plant Biosystems 144: 130-147.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(110)

Marziliano PA, Antonucci S, Tognetti R, Marchetti M, Chirici G, Corona P, Lombardi F (2021). Factors affecting the quantity and type of tree-related microhabitats in Mediterranean mountain forests of high nature value. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 14: 250-259.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(111)

Marziliano PA, Coletta V, Scuderi A, Scalise C, Menguzzato G, Lombardi F (2017). Forest structure of a maple old-growth stand: a case study on the Apennines mountains (Southern Italy). Journal of Mountain Science 14: 1329-40.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(112)

Mason F, Zapponi L (2016). The forest biodiversity artery: towards forest management for saproxylic conservation. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 9: 205-216.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(113)

Matteucci E, Benesperi R, Giordani P, Piervittori R, Isocrono D (2012). Epiphytic lichen communities in chestnut stands in Central-North Italy. Biologia 67: 61-70.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(114)

Maurizi E, Campanaro A, Chiari S, Maura M, Mosconi F, Sabatelli S, Zauli A, Audisio P, Carpaneto GM, Maurizi E, Campanaro A, Chiari S, Maura M, Mosconi F, Sabatelli S, Zauli A, Audisio P, Carpaneto GM, Maurizi E, Campanaro A, Chiari S, Maura M, Mosconi F, Sabatelli S, Zauli A, Audisio P, Carpaneto GM (2017). Guidelines for the monitoring of Osmoderma eremita and closely related species. Nature Conservation 20 (3): 79-128.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(115)

McRoberts RE, Winter S, Chirici G, Lapoint E (2012). Assessing forest naturalness. Forest Science 58: 294-309.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(116)

Mercer C, Comeau VM, Daniels LD, Carrer M (2022). Contrasting impacts of climate warming on coastal old-growth tree species reveal an early warning of forest decline. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 4: 7063.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(117)

Mikolas M, Svitok M, Bace R, Meigs GW, Keeton WS, Keith H, Buechling A, Trotsiuk V, Kozak D, Bollmann K, Begovic K, Cada V, Chaskovskyy O, Ralhan D, Dusatko M, Ferencik M, Frankovic M, Gloor R, Hofmeister J, Janda P, Kameniar O, Labusova J, Majdanova L, Nagel TA, Pavlin J, Pettit JL, Rodrigo R, Roibu CC, Rydval M, Sabatini FM, Schurman J, Synek M, Vostarek O, Zemlerova V, Svoboda M (2021). Natural disturbance impacts on trade-offs and co-benefits of forest biodiversity and carbon. Proceedings of the Royal Society B - Biological Sciences 288.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(118)

Morales-Molino C, Steffen M, Samartin S, Van Leeuwen JFN, Hurlimann D, Vescovi E, Tinner W (2021). Long-term responses of Mediterranean mountain forests to climate change, fire and human activities in the Northern Apennines (Italy). Ecosystems 24: 1361-1377.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(119)

Motta R (2002). Old-growth forests and silviculture in the Italian Alps: the case-study of the strict reserve of Paneveggio (TN). Plant Biosystems 136: 223-231.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(120)

Motta R, Berretti R, Castagneri D, Dukic V, Garbarino M, Govedar Z, Lingua E, Maunaga Z, Meloni F (2011). Toward a definition of the range of variability of central European mixed Fagus-Abies-Picea forests: the nearly steady-state forest of Lom (Bosnia and Herzegovina). Canadian Journal of Forest Research 41: 1871-1884.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(121)

Motta R, Nola P (2001). Growth trends and dynamics in sub-alpine forest stands in the Varaita Valley (Piedmont, Italy) and their relationships with human activities and global change. Journal of Vegetation Science 12: 219-230.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(122)

Motta R, Nola P, Piussi P (2002). Long-term investigations in a strict forest reserve in the eastern Italian Alps: spatio-temporal origin and development in two multi-layered subalpine stands. Journal of Ecology 90: 495-507.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(123)

Motta R, Garbarino F (2003). Stand history and its consequences for the present and future dynamic in two silver fir (Abies alba Mill.) stands in the high Pesio Valley (Piedmont, Italy). Annals of Forest Science 60: 361-370.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(124)

Motta R, Berretti R, Castagneri D, Lingua E, Nola P, Vacchiano G (2010). Stand and coarse woody debris dynamics in subalpine Norway spruce forests withdrawn from regular management. Annals of Forest Science 67 (8): 803-803.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(125)

Motta R, Garbarino M, Berretti R, Bjelanovic I, Mondino EB, Curovic M, Keren S, Meloni F, Nosenzo A (2015a). Structure, spatio-temporal dynamics and disturbance regime of the mixed beech-silver fir-Norway spruce old-growth forest of Biogradska Gora (Montenegro). Plant Biosystems 149: 966-975.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(126)

Motta R, Garbarino M, Berretti R, Meloni F, Nosenzo A, Vacchiano G (2015b). Development of old-growth characteristics in uneven-aged forests of the Italian Alps. European Journal of Forest Research 134: 19-31.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(127)

Muggia L, Kati V, Rohrer A, Halley J, Mayrhofer H (2018). Species diversity of lichens in the sacred groves of Epirus (Greece). Herzogia 31: 231-244.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(128)

Muscolo A, Bagnato S, Sidari M, Mercurio R (2014). A review of the roles of forest canopy gaps. Journal of Forestry Research 25: 725-736.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(129)

Nascimbene J, Marini L, Nimis PL (2007). Influence of forest management on epiphytic lichens in a temperate beech forest of northern Italy. Forest Ecology and Management 247: 43-47.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(130)

Nascimbene J, Marini L, Carrer M, Motta R, Nimis PL (2008a). Influences of tree age and tree structure on the macrolichen Letharia vulpina: A case study in the Italian Alps. Ecoscience 15: 423-428.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(131)

Nascimbene J, Marini L, Motta R, Nimis PL (2008b). Lichen diversity of coarse woody habitats in a Pinus-Larix stand in the Italian Alps. Lichenologist 40: 153-163.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(132)

Nascimbene J, Marini L, Nimis PL (2010). Epiphytic lichen diversity in old-growth and managed Picea abies stands in Alpine spruce forests. Forest Ecology and Management 260: 603-609.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(133)

Nascimbene J, Dainese M, Sitzia T (2013). Contrasting responses of epiphytic and dead wood-dwelling lichen diversity to forest management abandonment in silver fir mature woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 289: 325-332.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(134)

Nascimbene J, Nimis PL, Dainese M (2014). Epiphytic lichen conservation in the Italian Alps: the role of forest type. Fungal Ecology 11: 164-172.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(135)

Nascimbene J, Gheza G, Hafellner J, Mayrhofer H, Muggia L, Obermayer W, Thor G, Nimis PL (2021). Refining the picture: new records to the lichen biota of Italy. MycoKeys 82 (3): 97-137.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(136)

Nimis PL, Martellos S, Spitale D, Nascimbene J (2018). Exploring patterns of commonness and rarity in lichens: a case study from Italy (Southern Europe). Lichenologist 50: 385-396.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(137)

Paffetti D, Travaglini D, Buonamici A, Nocentini S, Vendramin GG, Giannini R, Vettori C (2012). The influence of forest management on beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) stand structure and genetic diversity. Forest Ecology and Management 284: 34-44.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(138)

Palandrani C, Motta R, Cherubini P, Curovic M, Dukic V, Tonon G, Ceccon C, Peressotti A, Alberti G (2021). Role of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance on the long-term rising of intrinsic water use efficiency in dominant trees in three old-growth forests in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Montenegro. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 14: 53-60.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(139)

Parisi F, Innangi M, Tognetti R, Lombardi F, Chirici G, Marchetti M (2021). Forest stand structure and coarse woody debris determine the biodiversity of beetle communities in Mediterranean mountain beech forests. Global Ecology and Conservation 28: e01637.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(140)

Persiani AM, Audisio P, Lunghini D, Maggi O, Granito VM, Biscaccianti AB, Chiavetta U, Marchetti M (2010). Linking taxonomical and functional biodiversity of saproxylic fungi and beetles in broad-leaved forests in southern Italy with varying management histories. Plant Biosystems 144: 250-261.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(141)

Persiani AM, Lombardi F, Lunghini D, Granito VM, Tognetti R, Maggi O, Pioli S, Marchetti M (2016). Stand structure and deadwood amount influences saproxylic fungal biodiversity in Mediterranean mountain unmanaged forests. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 9: 115-124.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(142)

Petritan IC, Marzano R, Petritan AM, Lingua E (2014). Overstory succession in a mixed Quercus petraea-Fagus sylvatica old growth forest revealed through the spatial pattern of competition and mortality. Forest Ecology and Management 326: 9-17.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(143)

Pezzi G, Gambini S, Buldrini F, Ferretti F, Muzzi E, Maresi G, Nascimbene J (2020). Contrasting patterns of tree features, lichen, and plant diversity in managed and abandoned old-growth chestnut orchards of the northern Apennines (Italy). Forest Ecology and Management 470.

Google Scholar

(144)

Pichler V, Gomoryova E, Leuschner C, Homolak M, Abrudan IV, Pichlerova M, Strelcova K, Di Filippo A, Sitko R (2021). Parent material effect on soil organic carbon concentration under primeval European beech forests at a regional scale. Forests 12 (4): 405.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(145)

Piovesan G, Adams JM (2005). The evolutionary ecology of masting: does the environmental prediction hypothesis also have a role in mesic temperate forests? Ecological Research 20: 739-743.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(146)

Piovesan G, Di Filippo A, Alessandrini A, Biondi F, Schirone B (2005). Structure, dynamics and dendroecology of an old-growth Fagus forest in the Apennines. Journal of Vegetation Science 16: 13-28.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(147)

Piovesan G, Biondi F, Di Filippo A, Alessandrini A, Maugeri M (2008). Drought-driven growth reduction in old beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) forests of the central Apennines, Italy. Global Change Biology 14: 1265-1281.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(148)

Piovesan G, Saba EP, Biondi F, Alessandrini A, Di Filippo A, Schirone B (2009). Population ecology of yew (Taxus baccata L.) in the Central Apennines: spatial patterns and their relevance for conservation strategies. Plant Ecology 205: 23-46.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(149)

Piovesan G, Biondi F, Baliva M, Calcagnile L, Quarta G, Di Filippo A (2018). Dating old hollow trees by applying a multistep tree-ring and radiocarbon procedure to trunk and exposed roots. MethodsX 5: 495-502.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(150)

Piovesan G, Biondi F, Baliva M, De Vivo G, Marchiano V, Schettino A, Di Filippo A (2019). Lessons from the wild: slow but increasing long-term growth allows for maximum longevity in European beech. Ecology 100 (9): 727.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(151)

Puglisi M, Costa R, Privitera M (2012). Bryophyte coastal vegetation of the Cilento and Vallo di Diano National Park (S Italy) as a tool for ecosystem assessment. Plant Biosystems 146: 309-323.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(152)

Rassati D, Marini L, Malacrino A (2019). Acquisition of fungi from the environment modifies ambrosia beetle mycobiome during invasion. PeerJ 7: e8103.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(153)

Ravera S, Brunialti G (2013). Epiphytic lichens of a poorly explored National Park: is the probabilistic sampling effective to assess the occurrence of species of conservation concern? Plant Biosystems 147: 115-124.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(154)

Rondeux J, Bertini R, Bastrup-Birk A, Corona P, Latte N, McRoberts RE, Stahl G, Winter S, Chirici G (2012). Assessing deadwood using harmonized national forest inventory data. Forest Science 58: 269-283.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(155)

Rozendaal DMA, Suarez DR, De Sy V, Avitabile V, Carter S, Yao CYA, Alvarez-Davila E, Anderson-Teixeira K, Araujo-Murakami A, Arroyo L, Barca B, Baker TR, Birigazzi L, Bongers F, Branthomme A, Brienen RJW, Carreiras JMB, Gatti RC, Cook-Patton SC, Decuyper M, Devries B, Espejo AB, Feldpausch TR, Fox J, Gamarra JGP, Griscom BW, Harris N, Herault B, Coronado ENH, Jonckheere I, Konan E, Leavitt SM, Lewis SL, Lindsell JA, Marimon B, Mitchard ETA, Monteagudo A, Morel A, Pekkarinen A, Phillips OL, Poorter L, Qie L, Rutishauser E, Ryan CM, Santoro M, Silayo D, Sist P, Slik JWF, Sonke B, Sullivan MJP, Laurin GV, Vilanova E, Wang MMH, Zahabu E, Herold M (2022). Aboveground forest biomass varies across continents, ecological zones and successional stages: refined IPCC default values for tropical and subtropical forests. Environmental Research Letters 17 (1): 014047.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(156)

Ruiz-Lopez MJ, Barelli C, Rovero F, Hodges K, Roos C, Peterman WE, Ting N (2016). A novel landscape genetic approach demonstrates the effects of human disturbance on the Udzungwa red colobus monkey (Procolobus gordonorum). Heredity 116: 167-176.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(157)

Sabatini FM, Burrascano S, Tuomisto H, Blasi C (2014a). Ground layer plant species turnover and beta diversity in Southern-European old-growth forests. PLoS One 9 (4): e95244.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(158)

Sabatini FM, Burton JI, Scheller RM, Amatangelo KL, Mladenoff DJ (2014b). Functional diversity of ground-layer plant communities in old-growth and managed northern hardwood forests. Applied Vegetation Science 17: 398-407.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(159)

Sabatini FM, Jimenez-Alfaro B, Burrascano S, Blasi C (2014c). Drivers of herb-layer species diversity in two unmanaged temperate forests in northern Spain. Community Ecology 15: 147-157.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(160)

Sabatini FM, Burrascano S, Lombardi F, Chirici G, Blasi C (2015a). An index of structural complexity for Apennine beech forests. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 8: 314-323.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(161)

Sabatini FM, Zanini M, Dowgiallo G, Burrascano S (2015b). Multiscale heterogeneity of topsoil properties in southern European old-growth forests. European Journal of Forest Research 134: 911-925.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(162)

Sabatini FM, Burrascano S, Keeton WS, Levers C, Lindner M, Potzschner F, Verkerk PJ, Bauhus J, Buchwald E, Chaskovsky O, Debaive N, Horvath F, Garbarino M, Grigoriadis N, Lombardi F, Duarte IM, Meyer P, Midteng R, Mikac S, Mikolas M, Motta R, Mozgeris G, Nunes L, Panayotov M, Odor P, Ruete A, Simovski B, Stillhard J, Svoboda M, Szwagrzyk J, Tikkanen OP, Volosyanchuk R, Vrska T, Zlatanov T, Kuemmerle T (2018). Where are Europe’s last primary forests? Diversity and Distributions 24: 1426-1439.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(163)

Sabatini FM, Keeton WS, Lindner M, Svoboda M, Verkerk PJ, Bauhus J, Bruelheide H, Burrascano S, Debaive N, Duarte I, Garbarino M, Grigoriadis N, Lombardi F, Mikolas M, Meyer P, Motta R, Mozgeris G, Nunes L, Odor P, Panayotov M, Ruete A, Simovski B, Stillhard J, Svensson J, Szwagrzyk J, Tikkanen OP, Vandekerkhove K, Volosyanchuk R, Vrska T, Zlatanov T, Kuemmerle T (2020). Protection gaps and restoration opportunities for primary forests in Europe. Diversity and Distributions 26: 1646-1662.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(164)

Sabatini FM, Bluhm H, Kun Z, Aksenov D, Atauri JA, Buchwald E, Burrascano S, Cateau E, Diku A, Duarte IM, Lopez ABF, Garbarino M, Grigoriadis N, Horvath F, Keren S, Kitenberga M, Kis A, Kraut A, Ibisch PL, Larrieu L, Lombardi F, Matovic B, Melu RN, Meyer P, Midteng R, Mikac S, Mikolas M, Mozgeris G, Panayotov M, Pisek R, Nunes L, Ruete A, Schickhofer M, Simovski B, Stillhard J, Stojanovic D, Szwagrzyk J, Tikkanen OP, Toromani E, Volosyanchuk R, Vrska T, Waldherr M, Yermokhin M, Zlatanov T, Zagidullina A, Kuemmerle T (2021). European primary forest database v2.0. Scientific Data 8: 220.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(165)

Santopuoli G, Vizzarri M, Spina P, Maesano M, Mugnozza GS, Lasserre B (2022). How individual tree characteristics and forest management influence occurrence and richness of tree-related microhabitats in Mediterranean mountain forests. Forest Ecology and Management 503 (1): 119780.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(166)

Scalercio S, Bonacci T, Turco R, Bernardini V (2016). Relationships between Psychidae communities (Lepidoptera: Tineoidea) and the ecological characteristics of old-growth forests in a beech dominated landscape. European Journal of Entomology 113: 113-121.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(167)

Scattolin L, Lancellotti E, Franceschini A, Montecchio L (2014). The ectomycorrhizal community in Mediterranean old-growth Quercus ilex forests along an altitudinal gradient. Plant Biosystems 148: 74-82.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(168)

Schirone B, Pedrotti F, Spada F, Bernabei M, Di Filippo A, Piovesan G (2005). The old-growth beech forest of Cervara valley (National park of Abruzzes, Italy). Acta Botanica Gallica 152: 519-528.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(169)

Schulze ED, Mischi G, Asche G, Borner A (2007). Land-use history and succession of Larix decidua in the Southern Alps of Italy - An essay based on a cultural history study of Roswitha Asche. Flora 202: 705-713.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(170)

Seidling W, Travaglini D, Meyer P, Waldner P, Fischer R, Granke O, Chirici G, Corona P (2014). Dead wood and stand structure - relationships for forest plots across Europe. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 7: 269-81.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(171)

Sitzia T, Trentanovi G, Dainese M, Gobbo G, Lingua E, Sommacal M (2012). Stand structure and plant species diversity in managed and abandoned silver fir mature woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 270: 232-238.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(172)

Sitzia T, Campagnaro T, Gatti E, Sommacal M, Kotze DJ (2015). Wildlife conservation through forestry abandonment: responses of beetle communities to habitat change in the Eastern Alps. European Journal of Forest Research 134: 511-524.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(173)

Solano E, Mancini E, Ciucci P, Mason F, Audisio P, Antonini G (2013). The EU protected taxon Morimus funereus Mulsant, 1862 (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) and its western Palaearctic allies: systematics and conservation outcomes. Conservation Genetics 14: 683-694.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(174)

Solano F, Pratico S, Piovesan G, Modica G (2021). Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) derived canopy gaps in the old-growth beech forest of Mount Pollinello (Italy): preliminary results. In: “Computational Science and Its Applications - ICCSA 2021: 21st International Conference, Cagliari, Italy, September 13-16, 2021, Proceedings, Part VII” (Gervasi O, Murgante B, Misra S, Garau C, Blečić I, Taniar D, Apduhan BO, Rocha AM, Tarantino E, Torre CM eds). Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 12, Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland, pp. 126-138.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(175)

Soliani C, Vendramin GG, Gallo LA, Marchelli P (2016). Logging by selective extraction of best trees: does it change patterns of genetic diversity? The case of Nothofagus pumilio. Forest Ecology and Management 373: 81-92.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(176)

Taffetani F, Catorci A, Ciaschetti G, Cutini M, Di Martino L, Frattaroli AR, Paura B, Pirone G, Rismondo M, Zitti S (2012). The Quercus cerris woods of the alliance Carpinion orientalis Horvat 1958 in Italy. Plant Biosystems 146: 918-953.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(177)

Tavankar F, Nikooy M, Picchio R, Venanzi R, Lo Monaco A (2017). Long-term effects of single-tree selection cutting management on coarse woody debris in natural mixed beech stands in the Caspian forest (Iran). iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 10: 652-58.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(178)

Teobaldelli M, Cona F, Stinca A, Saulino L, Anzano E, Giordano D, Migliozzi A, Bonanomi G, Mazzoleni S, Saracino A (2020). Improving resilience of an old-growth urban forest in Southern Italy: lesson(s) from a stand-replacing windstorm. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 47 (1): 126521.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(179)

Tini M, Bardiani M, Campanaro A, Chiari S, Mason F, Maurizi E, Toni I, Audisio P, Carpaneto GM (2017a). A stag beetle’s life: sex-related differences in daily activity and behaviour of Lucanus cervus (Coleoptera: Lucanidae). Journal of Insect Conservation 21: 897-906.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(180)

Tini M, Bardiani M, Campanaro A, Mason F, Audisio P, Carpaneto GM (2017b). Detection of stag beetle oviposition sites by combining telemetry and emergence traps. Nature Conservation 19: 81-96.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(181)

Tini M, Bardiani M, Chiari S, Campanaro A, Maurizi E, Toni I, Mason F, Audisio PA, Carpaneto GM (2018). Use of space and dispersal ability of a flagship saproxylic insect: a telemetric study of the stag beetle (Lucanus cervus) in a relict lowland forest. Insect Conservation and Diversity 11: 116-129.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(182)

Tomao A, Bonet JA, Castano C, De-Miguel S (2020). How does forest management affect fungal diversity and community composition? Current knowledge and future perspectives for the conservation of forest fungi. Forest Ecology and Management 457: 117678.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(183)

Tonon G, Dezi S, Ventura M, Scandellari F (2011). The effect of forest management on soil organic carbon. In: “Sustaining soil productivity in response to global climate change: Science, Policy, and Ethics” (Sauer TJ, Norman JM, Sivakumar MVK eds). Wiley, pp. 225-238

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(184)

Travaglini D, Paffetti D, Bianchi L, Bottacci A, Bottalico F, Giovannini G, Maltoni A, Nocentini S, Vettori C, Calamini G (2012). Characterization, structure and genetic dating of an old-growth beech-fir forest in the northern Apennines (Italy). Plant Biosystems 146: 175-188.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(185)

Trizzino M, Bisi F, Morelli CE, Preatoni DG, Wauters LA, Martinoli A (2014). Spatial niche partitioning of two saproxylic sibling species (Coleoptera, Cetoniidae, genus Gnorimus). Insect Conservation and Diversity 7: 223-231.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(186)

Vacchiano G, Meloni F, Ferrarato M, Freppaz M, Chiaretta G, Motta R, Lonati M (2016). Frequent coppicing deteriorates the conservation status of black alder forests in the Po plain (northern Italy). Forest Ecology and Management 382: 31-38.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(187)

Ziaco E, Alessandrini A, Blasi S, Di Filippo A, Dennis S, Piovesan G (2012a). Communicating old-growth forest through an educational trail. Biodiversity and Conservation 21: 131-144.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(188)

Ziaco E, Biondi F, Di Filippo A, Piovesan G (2012b). Biogeoclimatic influences on tree growth releases identified by the boundary line method in beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) populations of southern Europe. Forest Ecology and Management 286: 28-37.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar

(189)

Ziaco E, Di Filippo A, Alessandrini A, Baliva M, Piovesan G (2012c). Old-growth attributes in a network of Apennines (Italy) beech forests: Disentangling the role of past human interferences and biogeoclimate. Plant Biosystems 146: 153-166.

CrossRef |

Google Scholar